ARE Copyright Alert: U.S. Supreme Court Issues Ruling on the Application of the First Prong of Fair Use Defense

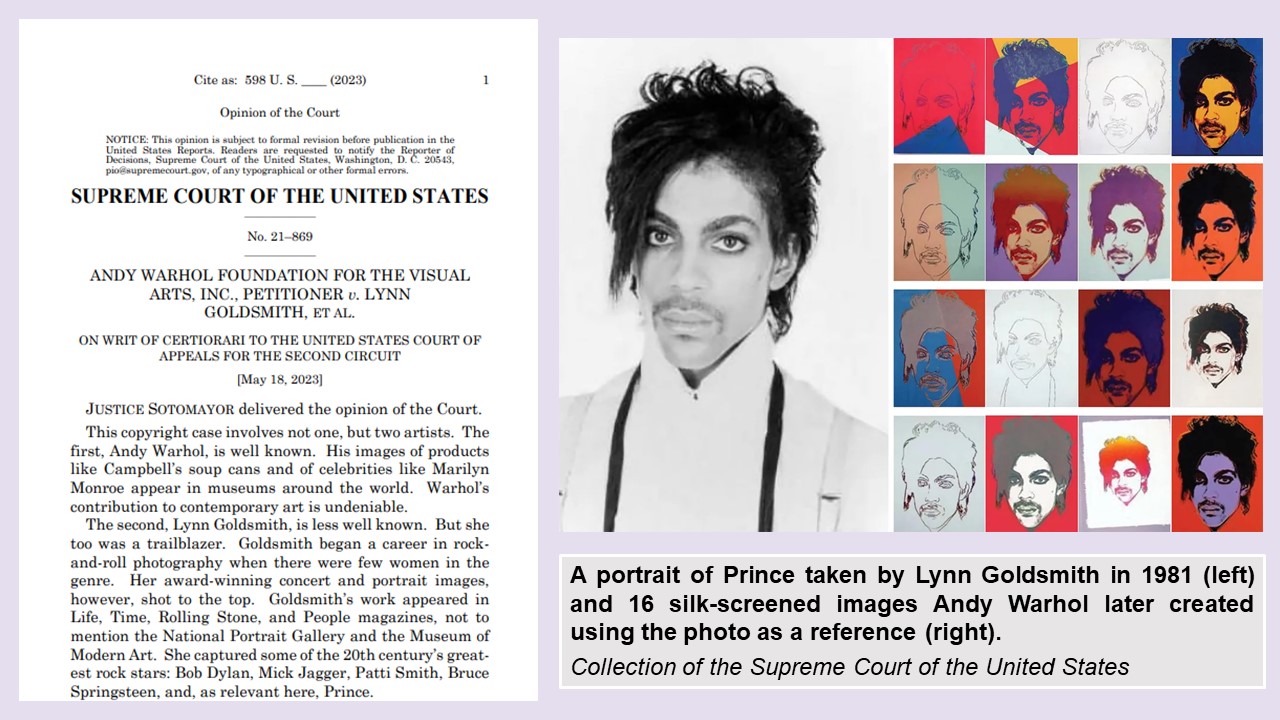

May 19, 2023On May 18, the Supreme Court issued a ruling in Andy Warhol Foundation for Visual Arts, Inc v. Goldsmith, No. 21-869, 598 U.S. _____ (2023), clarifying the scope of the first prong of the “fair use” defense to copyright infringement. In an opinion by Justice Sotomayor, the Court, 7-2, affirmed the ruling of the Second Circuit, holding that the “purpose and character” of the Andy Warhol Foundation’s particular commercial use of Lynn Goldsmith’s photograph does not favor AWF’s “fair use” defense to copyright infringement.

By way of background, in 1984, photographer Lynn Goldsmith granted a limited, one-time only license to Vanity Fair of a photograph she had taken of the musician Prince. Vanity Fair hired pop artist Andy Warhol to create an illustration of the photograph, resulting in a purple silkscreen which appeared on the cover of Vanity Fair’s November 1984 issue. Warhol created a total of sixteen works from the photograph, one of which was an orange silkscreen, known as “Orange Prince”. After Prince’s death in 2016, the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. (“AWF”) (which controls the intellectual property of the late Warhol) licensed to Condé Nast an image of “Orange Prince” to appear on the cover Vanity Fair’s issue commemorating Prince. Goldsmith and AWF entered into litigation, with Goldsmith alleging that AWF’s use of Goldsmith’s photograph constituted copyright infringement, and AWF claiming fair use.

While the District Court granted AWF summary judgment on its defense of fair use, the Second Circuit reversed, finding that all four fair use factors favored Goldsmith. The Supreme Court granted certiorari on the sole question of whether the first fair use factor, “the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes”, 17 U.S.C. §107(1), weighed in favor of AWF’s commercial license to Condé Nast of an image of Orange Prince.

In the majority opinion authored by Justice Sotomayor and joined by Justices Thomas, Alito, Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, Barrett, and Jackson, the Court held that it did not, affirming the Second Circuit ruling. Relying on its precedent, including its opinion in Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., 510 U.S. 569 (1994), the Court noted that the “first fair use factor considers whether the use of a copyrighted work has a further purpose or different character, which is a matter of degree, and the degree of difference must be balanced against the commercial nature of the use.” Goldsmith, majority slip op., at 15. Accordingly, where “an original work and a secondary use share the same or highly similar purposes, and the secondary use is of a commercial nature, the first factor is likely to weigh against fair use, absent some other justification for copying.” Id.

Applying this reasoning, the Court found that the first factor did not favor fair use. According to the Court, the purpose of the works is similar, as they are both “portraits of Prince used in magazines to illustrate stories about Prince”, id., majorityslip op., at 22-23, and AWFs use – licensing the photograph – was commercial in nature. Further, while recognizing that the “meaning or message” of a secondary work, to the extent it can be reasonably perceived, “is relevant to . . . purpose,” the Court noted that it was not dispositive. Id. at 31. Here, any difference in meaning was not, standing alone, enough to resolve the first factor in favor of a finding of fair use, particularly given the commercial context.

Additionally, in a footnote, the Court clarified that this outcome was consistent with its holding in Google LLC v. Oracle America, Inc., 141 S. Ct. 1183 (2021), where the Court found that placing Oracle’s code in a new context (i.e. mobile devices), given the necessity of use and context of the case, was fair use. Goldsmith, majorityslip op., at 30, n. 18. The Court did not engage in a significant comparison of the facts of the cases, however.

Justice Gorsuch, joined by Justice Jackson, authored a concurring opinion, interpreting the question as a “narrow one of statutory interpretation” and opining that the issue was one of “which ‘purpose’ and ‘character’ counts”—“the purpose the creator had in mind when producing his work and the character of his resulting work” or “the purpose and character of the challenged use.” See id., concurrenceslip op., at 1-2 (emphasis in original). Because the law does not require “judges to try their hand at art criticism” but to instead focus on “the particular use under challenge”, the Court’s decision was correct due to the significant overlap in purpose and use between AWF’s challenged use and Goldsmith’s protected use. Id. at 2.

Justice Kagan, joined by Chief Justice Roberts, dissented, casting the majority’s opinion as a “doctrinal shift” resting more on ipse dixit than sound legal reasoning, and which “undermines creative freedom” by emphasizing the similarity in commercial use in the two works. Id., dissent slip op., at 3-4. The dissent points to precedent – in Campbell and Google – suggesting that transformative copying qualifies as fair use, and pointed towards the transformative nature of Warhol’s work to suggest that the majority was mistaken in its analysis.

The dissent also takes a broad stance on the importance of follow-on works and the way fair use protects them. The dissent’s opinion describes the ways in which follow-on works can be transformative, pointing to, as one example of many, a series of paintings surrounding the reclining nude, and reflecting sardonically that “the majority would presumably describe the purposes to be “just two portraits of reclining nudes painted to sell to patrons.” See id., dissentslip op., at 31. In the dissent’s opinion, fair use exists to protect the creativity in these works, and “[t]he majority’s commercialism-trumps-creativity analysis”, id. at 19, in determining transformative use “will stifle creativity of every sort.” Id. at 36.

In response, the majority argued that “the Court’s decision, which is consistent with longstanding principles of fair use,” would not “snuff out the light of Western civilization”, and that the dissent’s “single-minded focus on the value of copying ignores the value of original works.” Id., majority slip op., at 36-37. In the majority’s telling, “the existing copyright law, of which today’s opinion is a continuation, is a powerful engine of creativity.” Id. at 37.

While the Court in Goldsmith, as it did in Google, thus suggested that its opinion was consistent with settled copyright law, the exact effect of its opinion, and whether it instead, as the dissent suggests, represents a “doctrinal shift,” remains to be seen.

We will continue to monitor the development of the fair use doctrine and provide further updates as courts throughout the country begin the task of interpreting and applying Goldsmith.

Charles R. Macedo is a partner, Olivia Harris is an associate, and Thomas Hart is a law clerk at Amster, Rothstein & Ebenstein LLP. Their practices specialize in all aspects of intellectual property law, including trademarks, copyrights and patents. They can be reached at [email protected], [email protected] and [email protected] respectively.

View all ARELaw Alerts

Upcoming Events

-

April 30, 2024 – May 2, 2024

AUTM Canadian Region Meeting 2024Location: Doubletree by Hilton Toronto Downtown, Toronto, Ontario (Registration Required)Speaker(s): Charles R. Macedo,

RSS FEED

Never miss another publication. Our RSS feed (what is RSS?) will inform you when new articles have been posted.

![]() Subscribe now!

Subscribe now!